Dostoevsky's Answer to Nihilism

Is a conservative response better than a liberal one?

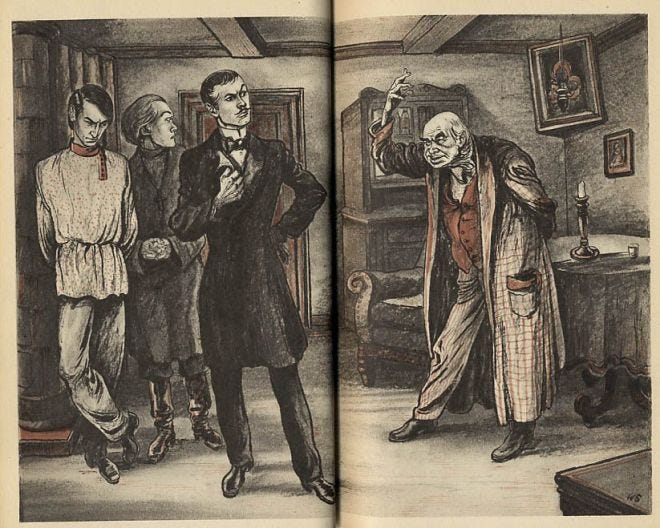

My brother and my girlfriend are huge Dostoevsky fans. I am fond of the writer myself, having participated in a 2021 Humanities at Hertog seminar with Prof. Howland on Dostoevsky's Demons. In the reading group, I appreciated the reductio ad absurdum critique leveled against nihilists through characters like Stavrogin. Mostly, though, I found the novel painfully slow-going and not particularly memorable. I'm sure this is mostly due to my lack of intellectual maturity at the time of reading. Luckily, as I move on to Part II of The Brothers Karamazov, I am thoroughly enjoying the plot of Dostoevsky's seminal work.

Dostoevsky joins Ayn Rand on my list of favorite anti-nihilist, pro-life novelists. Of peculiar interest is the fact that these two thinkers share virtually no branch of philosophy in common. Dostoevsky is something of a mystical, altruistic, communitarian while Ayn Rand is a realist, egoistic, individualist. The former rejects the Enlightenment and modernity while the other embraces it. The two opt for opposite strategies to combat postmodernism, communism, and nihilism. Which strategy is more effective? Can the two be synthesized?

I, unsurprisingly, believe the latter to be the philosophically defensible and pragmatic route and the former to be poetic and superficially convincing but, upon further inspection, epistemically bankrupt and nihilism-inducing. Regardless, I do admire the pillars of virtue Dostoevsky presents the reader: Father Zosima and Alyosha. Both are clergymen who are dedicated to faith, sacrifice, and altruism. Both are good-natured, honest, courageous, upstanding men whom I would be happy to call my friends. Is this not curious!? I am excited to continue investigating how I can find so much virtue in those whose most fundamental values I do not share. I suspect that the answer to this apparent paradox is that one judges others by their actions, which do spring from their beliefs, but not their beliefs directly. Therefore, if Zosima and Alyosha act out their contrary values, somehow, in a way that parallels the behavior I would prescribe for myself, then it makes sense for me to feel a strong affinity toward them. For example, this line from Zosima could have just as easily been uttered by Rand's Roark, Rearden, or Dagny Taggart:

I refuse to accept that the answer is as simple and idiotic as "the enemy of my enemy is my friend." No. The communist is not my friend because he is also the enemy of the fascist. They are simply both my sworn enemies, provided they do not change their belief systems and correct the error of their ways.

I have recently applied to another Humanities at Hertog reading group. This one would also be taught by Prof. Howland on a work by Dostoevsky: Notes From Underground. This novel is one of Dostoevsky's most pithy works and is my brother's absolute favorite. If I am accepted to the book group, I am excited to report my thoughts regarding the competition between conservatism and liberalism in confronting nihilism. If I am not accepted, I will read it anyway and also share my thoughts here! A win-win situation for my cherished readers.