Emerson: History, Fiction, and Biography

Ralph Waldo Emerson's "History" explains the philosophical importance of stories.

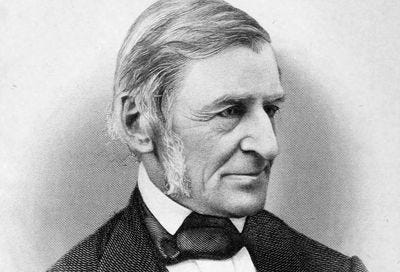

Per my brilliant brother’s recommendation, I finally got around to reading “History” (1841) by the transcendentalist writer Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson begins his essay with a decidedly Cartesian statement: “There is one mind common to all individual men.” The thinking substance common to all men “once admitted to the right of reason” enables the “freeman” to understand historical, mythical, and narratives of pure fiction through our personal experience:

We, as we read, must become Greeks, Romans, Turks, priest and king, martyr and executioner; must fast these images to some reality in our secret experience, or we shall learn nothing rightly… I can see my own vices without heat in the distant persons of Solomon, Alcibiades, and Catiline.

I admit that I am far less well-read in the Western canon than Emerson. I trust the reader will permit my youth excuse my relative and absolute ignorance. I see my own vices not in the characters of Solomon, Alcibiades, and Catiline but my insecurity in Shinji from Neon Genesis: Evangelion, my despair in Sasuke from Naruto: Shippuden, and my struggle against my inner demons in Peter Parker’s struggle against the venom symbiote in Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 3.

We also locate our goodness and potential therefor in the characters’ virtue:

All that Shakespeare says of the king, yonder slip of a boy that reads in the corner feels to be true of himself… He hears the commendation, not of himself, but, more sweet, of that character he seek, in every word that is said concerning character…

To Emerson, it is within our private experience, our “secret biography,” that we verify, understand, integrate “the emphatic facts of history.” In this way, Emerson goes so far as to claim that “there is properly no history, only biography.” When we read history, as when we read great (or even mediocre) works of fiction,

“we aim to master intellectually the steps and reach the same height or the same degradation that our fellow, our proxy has done.”

No wonder people find art depicting the fall from grace to be so compelling. By watching Lucifer, God’s own archangel, transform into the Prince of Darkness, as we watch the First Man plummet from Heaven to Hell, we think of our own pre- and post-lapsarian states. We meditate about how we can avoid succumbing to the very same vices that ruined men possessing the same mind we all share in common.

In poems, fables, myths, and other works of fiction, as in history, the identity

“is equally intrinsic, the diversity equally obvious. There is, at the surface, infinite variety of things; at the centre there is simplicity of cause.”

The jealously that corrupts Shakespeare’s noble Coriolanus is the very same that turns Lucas’s Anakin Skywalker to the Dark Side of the Force. In short, “Nature is an endless combination and repetition of a very few laws.” The ubiquity of these natural laws is what makes “all public facts… to be individualized, all private facts… to be generalized. Then at once History becomes fluid and true, and Biography deep and sublime.” The tight union between History and Biography explains why man cannot “find any antiquity” in the “voice of prophet[s]” dead for millenia; their words merely of antiquity “ech[o] to [man] a sentiment of his infancy.”

In my early youth, I didn’t understand why I spent so much time in school reading fiction and ancient (or even recent) history. As I’ve gotten older and matured intellectually (at least, to some extent), I have discovered, as all people do, precisely the significance of studying fiction and history:

The advancing man discovers how deep a property he has in literature,—in all fable as well as in all history. He finds that the poet was no odd fellow who described strange and impossible situations, but that universal man wrote by his pen a confession true for one and true for all. His own secret biography he finds in lines wonderfully intellgible to him, dotted down before he was born.”

Beautiful fables present readers with “universal verities.” History and Fiction present their interpreter with formal truths that enable him to appreciate the sublimity of his personal experience. Stories from History and Fiction make “facts fall aptly and supple into their places” in man’s secret biography, providing him a greater understanding of himself. Emerson identifies why humans love reading fiction, watching movies, and viewing sculpture and art; they reveal himself to him.