I am not done writing about Puss in Boots: The Last Wish. In my first post, I explained how the film provides a succinct explanation of the economic concept of diminishing marginal value; the more lives Puss has, the less he values each of them.

In this post, I am going to explain how The Last Wish innovates on a literary trope dating back to—I must consult Google to determine when Virgil wrote the Aeneid—around 20BC (and probably before then in other cultures with which I am not familiar): the katabasis, a.k.a., journey through hell.

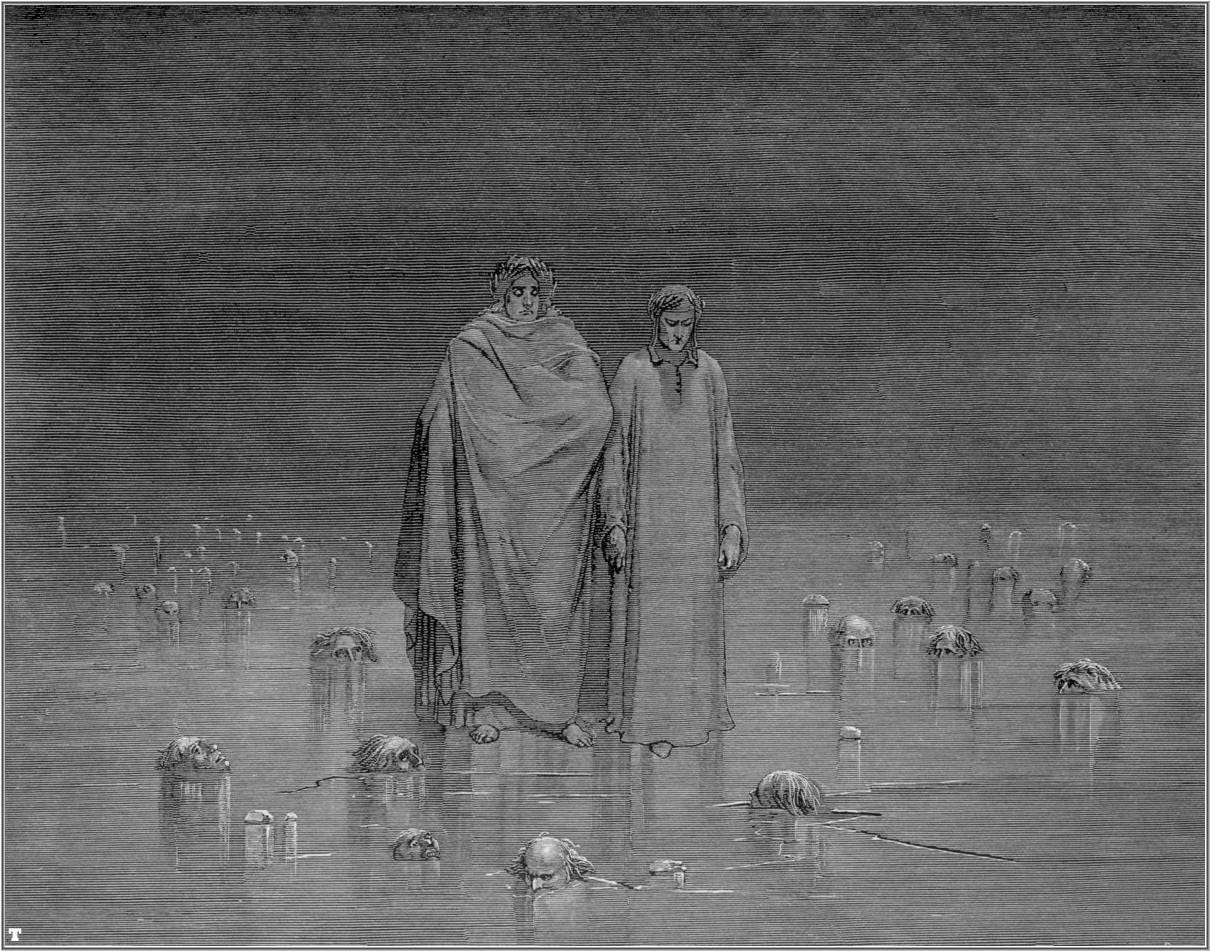

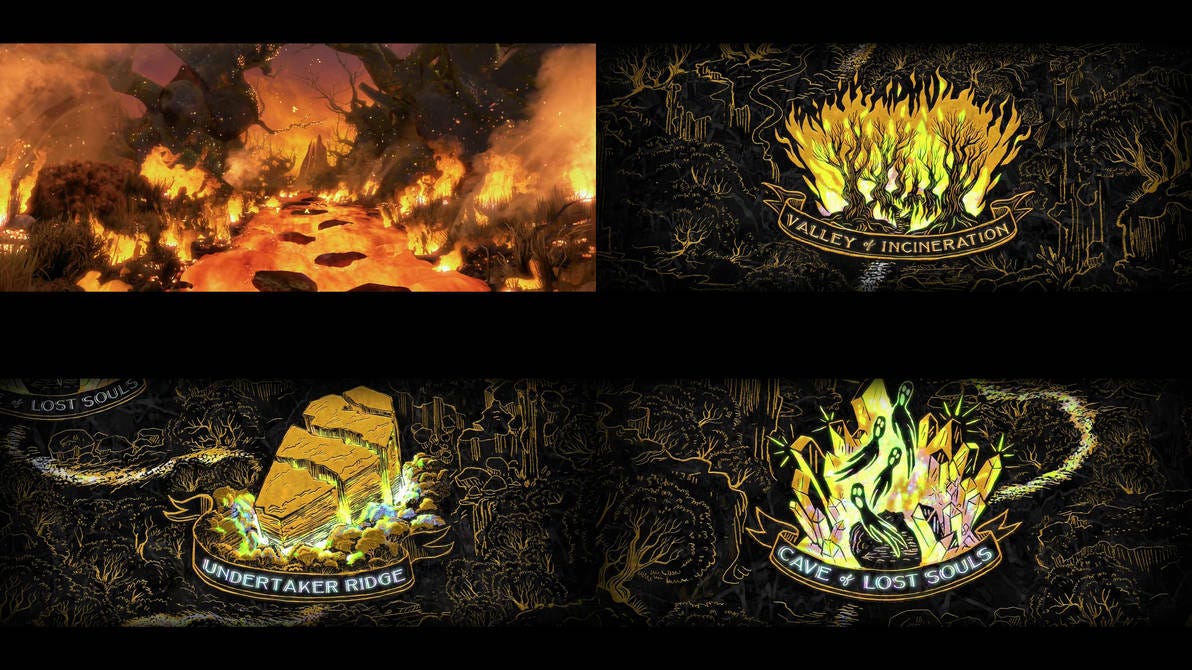

Dante’s Inferno, the first book of The Divine Comedy (1321AD), documents the author-protagonist’s journey through the nine circles of Judeo-Christian hell. Dante is accompanied by his literary and spiritual guide, Virgil, who ushers him through the pre-ordained hellscape. Analogously, Puss in Boots is accompanied by cherished companions as he journeys through the Dark Forest to the Fallen Star. However, and this is the exciting part, the Dark Forest is determined by whoever holds the map thereof. When Puss in Boots holds the map, it shows the Valley of Incineration, Undertaker Ridge, and the Cave of Lost Souls, reflecting his intense fear of death. When Kitty Softpaws holds the map, it reveals the Swamp of Infinite Sorrows, the Mountains of Misery, and The Abyss of Eternal Loneliness, reflecting her fear of heartbreak following her abandonment by Puss in Boots. Unlike Dante’s Inferno or Virgil’s Aeneid, the heroes must struggle through a hell of their own making… literally.

Virgil, Dante, and Puss in Boots’ katabases are inspirational stories in so far as they remind us that suffering is often prerequisite to growth, enlightenment, expansion, and the achievement of one’s highest aspirations. Dante’s Inferno and Puss in Boots emphasize that, as one proceeds through the bowels of hell, one must rely on the support, guidance, and companionship of one’s closest friends. Even when the path is idiosyncratic, Puss in Boots reminds us that we musn’t go it alone.