Year after year, consumers bemoan the rising price of goods. And with good reason: When the price of the stuff you buy increases by X% and your wage increases by less than X%, you are paying more in real terms (say, hours worked) for the same stuff.

Not so fun!

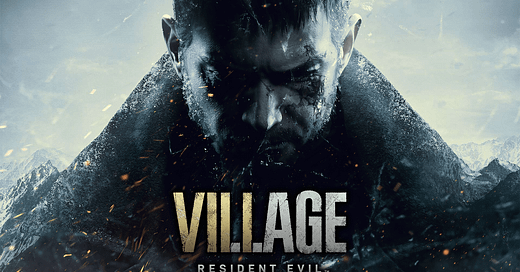

But one commodity has been priced the same for as long as I can remember. I’m only 22 years old, so that’s not saying a lot, but with a compounded annual interest rate of 2%, that means that a good that cost 1$ when I was in diapers should cost about $1.58 now. And yet, for as long as I can remember (let’s say, 6 years old), triple-A video games have cost $60. Assuming that people’s wages nominally increase by 2% each year to keep pace with inflation (I frankly don’t know how optimistic an assumption this is—labor economics isn’t my forte), gamers are spending less in real terms on titles in 2023 than they did in 2000.

TL;DR: games should cost about $95 but are sold for $60.

How come?

I think several factors are at play:

At the end of the day, games are a luxury good with relatively elastic demand. If producers jack up prices significantly, gamers will buy significantly less of the product in aggregate, making such a pricing decision not the profit-maximizing one.

Many games, particularly old ones, are durable goods. I am happy replaying Fallout: New Vegas for the sixth time, would be even more inclined to do so if the latest Fallout cost $100, and the same goes for many other gamers and myriad video game franchises.

Video game sellers have employed industrial organization techniques to have their consumers self-sort into high- and low-willingness to play types. To the former, sellers advertise a “complete,” “deluxe,” or “legendary” version of the game with DLC (downloadable content). To the latter, they offer the “base” game that offers a complete experiences but without as many hours of content, missions, collectibles, etc. The two versions of the game are vertically differentiated and sold to different consumers with different abilities to pay. Such price discrimination is surplus-maximizing (most is captured by the producer) and extends the market to those consumers with the lowest ability to pay.

Path dependency: Gamers are used to paying $60 for video games, think about prices in nominal terms, and would be outraged by developers setting a higher price, purchasing even fewer games to stick it to the devs.

I think option 3 is the most plausible, but no set of the above is mutually exclusive to another and each option probably contributes to video games remaining $60.