Why Don't We Complain?

Reflections on William F. Buckley Jr.'s 1961 Essay

An editor of a national weekly news magazine told me a few years ago that as few as a dozen letters of protest against an editorial stance of his magazine was enough to convene a plenipotentiary meeting of the board of editors to review policy. "So few people complain, or make their voices heard," he explained to me, "that we assume a dozen letters represent the unarticulated views of thousands of readers.”

…

When our voices are finally mute, when we have finally suppressed the natural instinct to complain, whether the vexation is trivial or grave, we shall have become automatons, incapable of feeling.

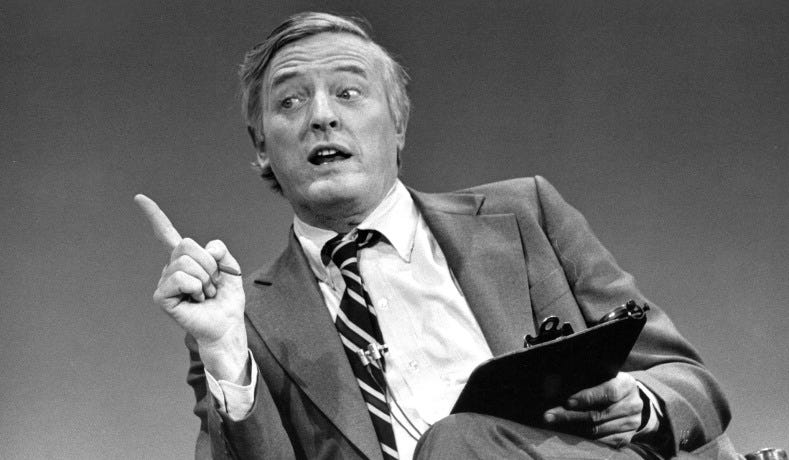

“Why Don’t We Complain?” was the first piece of writing of Buckley’s that I have read, courtesy of Dr. Tramantano, my junior AP English Language teacher at the Bronx High School of Science. Pithy and persuasive, Buckley’s lamentation struck such a chord with me at the time that I have revisited the essay half a decade later. Upon re-reading his essay, I was struck by the above excerpt.

More than six decades ago, William F. Buckley Jr. specified the chilling effect that “a dozen letters,” erroneously assumed to represent the prevailing attitude on a given matter, can produce in a news agency. In modern day, the equivalent of a dozen angry letters might be a hundred incendiary Tweets. Regardless of the format such missives assume, the lesson I glean from Buckley’s essay, among others, is that we must not allow vocal disapproval to alienate us from our intrinsic sense of right (and wrong). Instead, we must continue to express our honest convictions, irrespective of the approval or disapproval of any quantum of people.

The short essay, linked here, is worth reading (and re-reading) in full. It pays dividends.