Market-Preserving Federalism: US and China

Comparing MPF in the US and China from 2007 to 2020.

Today I would like to share my preliminary findings regarding the extent of market-preserving federalism in both China and the US. The motivation for this research is Econ 15: The Political Economy of China. In this course, my class and I have explored the liberalization of the Chinese economy from the death of Mao Zedong and the rise of Deng Xiaoping to the present Xi Jinping regime. As we studied the evolution of the Chinese economic and political system in class, I became increasingly interested in how the Chinese party-state, despite being politically authoritarian, has permitted and embraced market reforms following the end of Mao’s Cultural Revolution in 1976. Recalling the concept of market-preserving federalism from my summer course on Economies in Transition with Professor Rosolino Candela at George Mason University, I have sought to understand these reforms through this framework.

But what even is “market-preserving federalism”? Well, first of all, it’s quite a mouthful. I have taken to abbreviating it as MPF in my paper and will do so here. While descriptions vary, I have taken up Professor Barry Weingast’s1 conception of MPF as I believe it is the most detailed and comprehensive. Prof. Weingast’s MPF consists of the following 5 major features:

“(Fl) a hierarchy of governments, that is, at least ‘two levels of governments rule the same land and people,’ each with a delineated scope of authority so that each level of government is autonomous in its own, well-defined sphere of political authority; and (F2) the autonomy of each government is institutionalized in a manner that makes federalism's restrictions self-enforcing [via the following mechanisms]…(F3) subnational governments have primary regulatory responsibility over the economy; (F4) a common market is ensured, preventing the lower governments from using their regulatory authority to erect trade barriers against the goods and services from other political units; and (F5) the lower governments face a hard budget constraint, that is, they have neither the ability to print money nor access to unlimited credit.”2

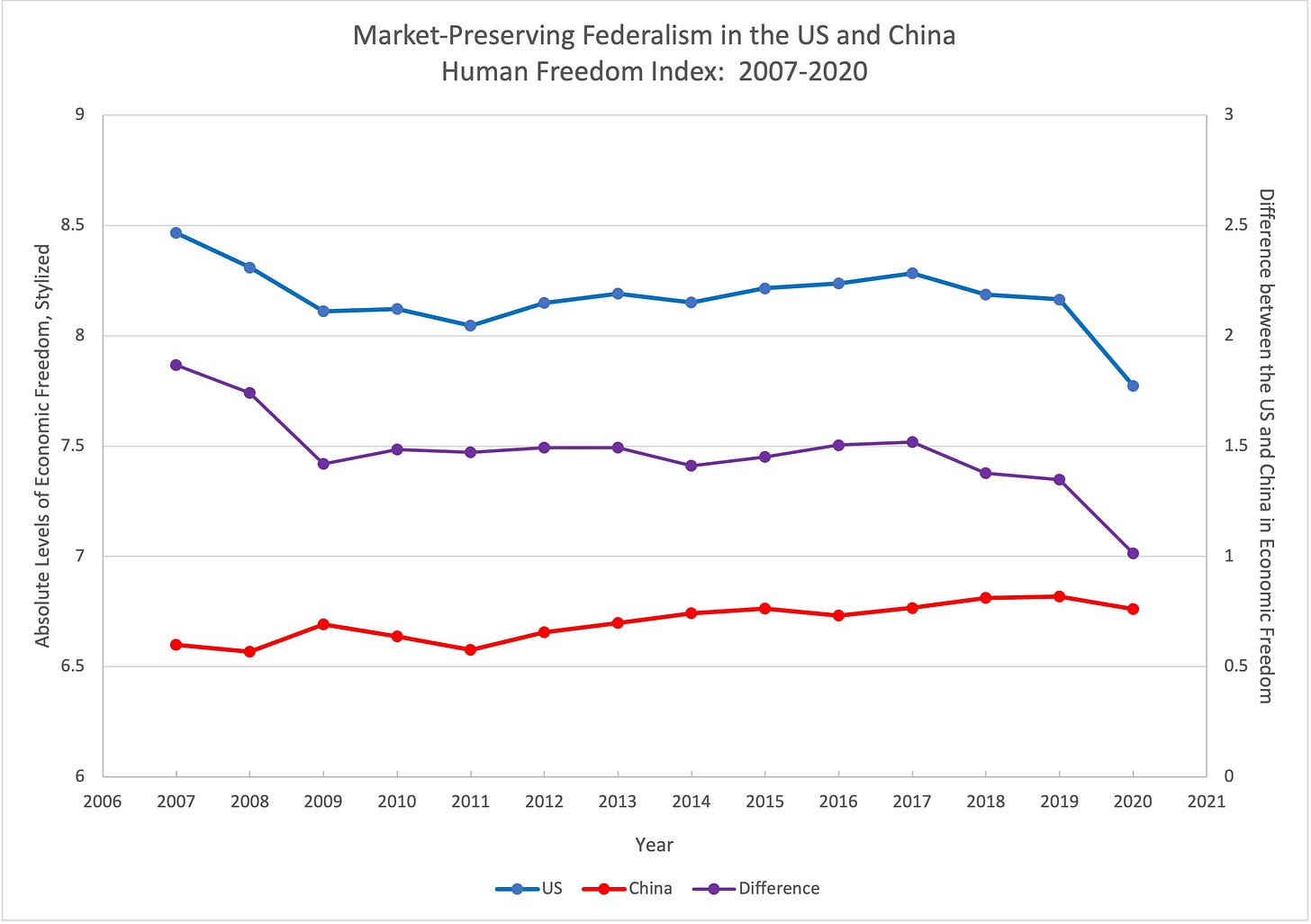

I will include a qualitative, historical comparison of MPF in the US and China in the 20th century. What follows is my attempt at a quantitative contemporary comparison between the two nations’ adoption of MPF using data from Cato’s 2022 Human Freedom Index (HFI). Cato’s index includes personal as well as economic freedom. While I appreciate the disparities in personal freedom between the two countries, my investigation is restricted to the degree of economic freedom in both countries. Rather than take the aggregate economic freedom indices of both nations, I selectively chose those factors that I found most relevant to the extent of MPF.

Cato’s HFI decomposes economic freedom into five categories, each determined by multiple factors: 1, “Size of Government” as instrumented by government consumption, transfers and subsidies, government investment, top marginal tax rate, state ownership of assets; 2, “Legal system and property rights” measured by judicial independence, impartial courts, protection of property rights, military interference, integrity of the legal system, legal enforcement of contracts, regulatory costs, and reliability of police; 3, “Sound money” measured by money growth, standard deviation of inflation, inflation (most recent year), and freedom to own foreign currency; 4, “Freedom to trade internationally” measured by tariffs, regulatory trade barriers, black-market exchange rates, and movement of capital and people; and 5, “Regulation” as composed of credit market, labor market, and business regulations.

I have bolded the factors that I selected to better gauge the extent to which the two nations practice MPF. Weingast’s definition of MPF places a particularly high premium on the presence of hard budget constraints, common markets, and subsidiarity of regulatory responsibility to local governments. I believe I chose the factors most germane to his conception of MPF but am, of course, eager to hear methodological challenges, critiques, and advice. Cato places equal weight on all five categories and, while I stylized the factors included in each, followed suit in my analysis. Consequently, my Excel equation (is not pretty) reads as follows:

AVERAGE(AVERAGE(BX#,CG#),AVERAGE(CK#,CN#,CO#),AVERAGE(CS#,CW#),AVERAGE(DG#,DJ#,DO#),AVERAGE(DT#,EA#,EH#))

Where BX is “All Transfers and subsidies”; CG is “Av State Ownership of Assets”; CK is “Biii Protection of property rights”; CN is “Bvi Legal enforcement of contracts”; CO is “Bvii Regulatory restrictions on the sale of real property”; CS is “Ci Money growth”; CW is “Ciii Inflation: Most recent year”; DG is “Di Tariffs”; DJ is “Dii Regulatory trade barriers”; DO is “Div Controls of the movement of capital and people”; DT is “Ei Credit market regulations”; EA is “Eii Labor market regulations”; and EH is “Eiii Business regulations.”

“#” is a placeholder for the country-year of the above variables. For example, China’s 2020 measure of “All Transfers and subsidies,” BX, is BX34. America’s 2020 measure of “All Transfers and subsidies” is BX160.

I chose the dates 2007-2020 because I wanted to capture the effect of the ‘08 financial crisis and 2020 is the most recent data featured in the report. I depict the results graphically below:

China has marginally improved since 2007, increasing from 6.60 and plateauing around 6.75 by 2020. The United States has witnessed a marked decline since 2007, falling from 8.47 to 7.77. The result is a nearly monotonic decrease in the difference between the two countries. While China has nominally improved in its implementation of MPF, the United States is losing ground; China isn’t becoming more like the US of old, the US is becoming more like China, i.e., less free. Depressingly, these data don’t include the further erosion of MPF resulting from multiple years of lockdown in both China and the US.

I solicit any and all feedback regarding my research question, methodology, and preliminary conclusions. Thanks for reading!

Barry R. Weingast is the Ward C. Krebs Family Professor, Department of Political Science, and a Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution. He served as Chair, Department of Political Science, from 1996 through 2001. He is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His full biography can be found here.

Weingast, Barry R. “The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development.” Journal of law, economics, & organization 11, no. 1 (1995): 4.