The True Cost of Rent-Seeking

Reviewing Gordon Tullock's seminal, "The Welfare Costs of Tariffs, Monopolies, and Theft."

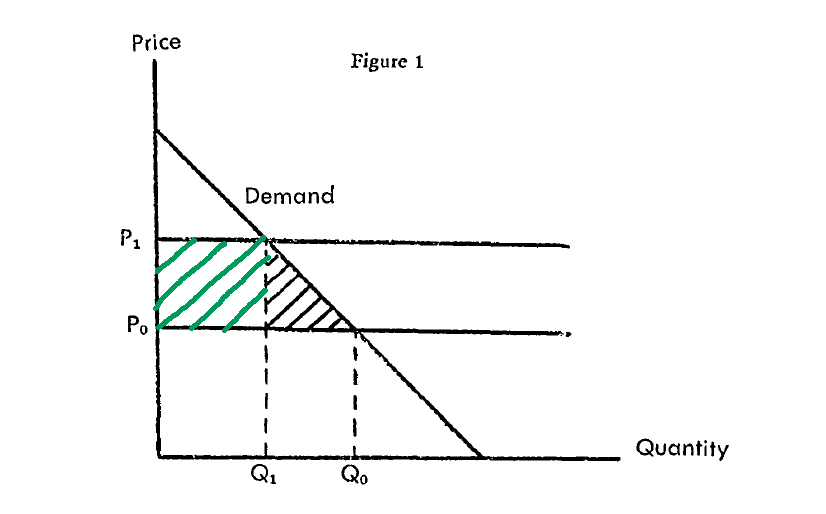

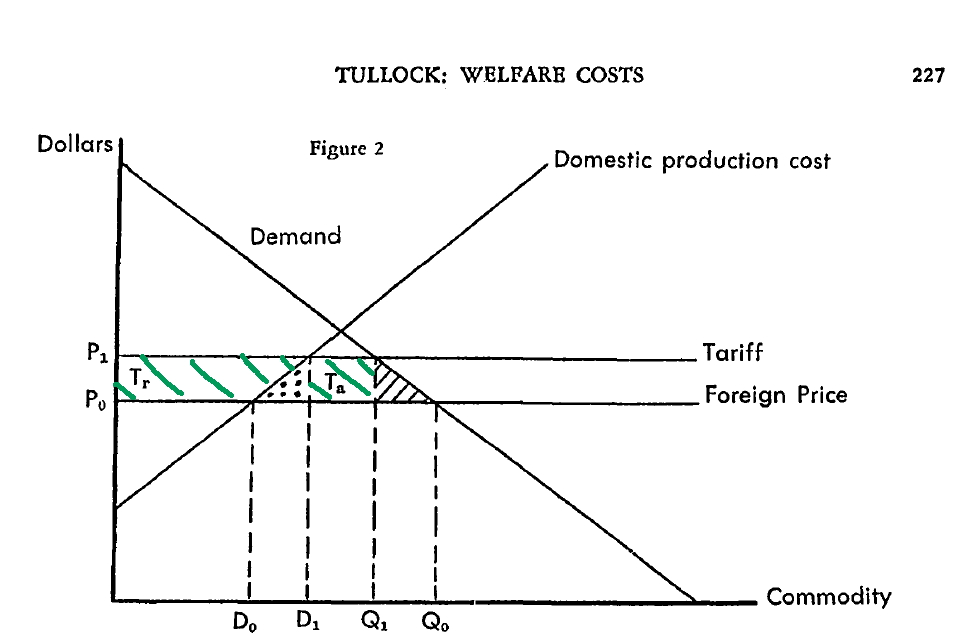

The Harberger triangle familiar to every student of economics is not the sum total of welfare lost to government intervention. As Tullock explains, one must consider the the producer surplus gained as welfare lost to society. Why? Well, Tullock brilliantly explains how this increased surplus represents the increased profitability of productively inefficient firms by imposing tariffs or excise taxes against foreign substitutes and/or provision of monopoly pricing. In effect, the producer surplus gained here is exactly the same as if the government were to, on the margin or entirely, depending on the excise/embargo, prevent a productively efficient domestic firm from competing with an inefficient one. That is, the state is distorting market signals to grow the market share of the inefficient firm at the expense of the more efficient one when capital would be better allocated elsewhere, e.g., the more productive firm. As Tullock reminds the reader, there is no economic difference between the more productive firm being “foreign” or “domestic.”

When the state accumulates tax revenue by imposing a tariff, we also cannot assume that this capital will be directed to its most highly-valued use. Perhaps it is rather uncharitable to suppose “that the revenues raised by this tax are completely wasted, building tunnels, for example, which go nowhere,” as Tullock does. Still, such caprice and misallocation of capital is inevitable given the lack of market forces. So, after one has regarded the artificially increased producer surplus, tax revenue, and Harberger triangle (measuring loss of consumer welfare), the deadweight loss of tariffs, excises, and monopolies becomes frighteningly large.

Unlike Harberger, Tullock does not assume that welfare transfers are frictionless. Through the reductio ad absurdum of theft, Tullock demonstrates how the seemingly purely frictionless transfer of funds from owner to thief is fraught with friction. The existence of thiefs means that capital will be allocated to locks, safes, and, most expensive of all, a combination of public and private police forces. Moreover, the thiefs themselves specialize in rent-seeking instead of profit-seeking, i.e., value transfer instead of value creation.

I highly recommend my readers to take a gander at Tullock’s pithy and incisive paper.1

Tullock, Gordon. “The Welfare Costs of Tariffs, Monopolies, and Theft.” Economic inquiry 5.3 (1967): 224–232. https://doi-org.dartmouth.idm.oclc.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.1967.tb01923.x